What are ghettos? According to Zygmunt Bauman, they are spaces of both physical and symbolic isolation, constructed not only through spatial boundaries but also through policies that delineate the “we” from the “others.” In practice, governmental approaches to minority populations have historically oscillated between two extreme strategies: complete assimilation or exclusion. One is expected either to conform to the dominant norm—white, nationalist, affluent, heteronormative male—or to vanish from the public sphere so as not to disturb its superficial homogeneity.

The practice of ghettoization is not new; it has a profound historical lineage. From the compulsory marking of Jews in medieval Europe to their forced conversion to Christianity in Spain, and from the Nazi ghettos—such as that of Łódź—to contemporary forms of exclusion, mechanisms of marginalization become entrenched whenever the coherence of a dominant national identity is perceived to be threatened, or as a means of imposing that identity. Today, ghettos emerge both from the human need for belonging and from the fear of an external threat—of the Other, the different—who is not approached with empathy but with rejection.

Within this context lies the concept of mixophobia—the fear of diversity, particularly in societies that, while operating under the conditions of globalization and cultural plurality, nonetheless seek uniformity. It is the fear of “mixing,” of coexistence and dialogue. As Bauman and Richard Sennett point out, homogeneity functions as a defense mechanism against complexity: it spares us the effort and discomfort of truly engaging with the Other. Thus, this fear is not merely individual but acquires political dimensions, infiltrating public policies and continuously reproducing exclusion.

A telling example of mixophobia was observed in Mytilene in 2020, upon the announcement of the construction of a new refugee camp, which triggered the now well-known episodes in both Mytilene and Chios. In a seemingly paradoxical scene, leftists protested alongside conservative citizens, albeit for entirely different reasons. The former demanded the refugees’ liberation from the camps and access to a better life; the latter called for their removal from the island, fearing for the region’s safety and “order.” What united them? The shared desire for the refugees’ removal—though the left saw them as excluded, while the conservatives saw them as a threat.

On Roma Ghettos

It is one thing to acknowledge the existence of deviant behavior, and quite another to attribute ethnic or cultural characteristics to social phenomena such as criminality. The collective condemnation of individuals who share cultural traits—through actions based on an externally imposed identity of the “criminal”—leads to exile, exclusion, and the criminalization of mere existence.

As Bauman notes in Liquid Love, citing Heather Grabbe, in wealthier European societies, blame for social problems is often displaced onto other nations. In contrast, in poorer societies, the enemy becomes internalized: always the newcomer, the marginalized—often, the Roma. The poorer the country, the more immediate and tangible the scapegoat.

The solution to the ghettoization of Roma communities—and others—cannot lie in repression, increased policing, or mass detentions, as is often proclaimed. Ghettos are not dismantled by labeling areas as “danger zones,” nor by targeting isolated “criminal elements.” Criminality is a complex social phenomenon requiring understanding, political will, and long-term structural interventions. What is needed is prevention—not the vicious cycle of fear and violence.

A preventative approach involves strengthening education, ensuring equal access to employment, and actively promoting social inclusion. Addressing the problem is not a matter of security, but of justice, social cohesion, and political adaptability.

The Other, the Wall, the Passage

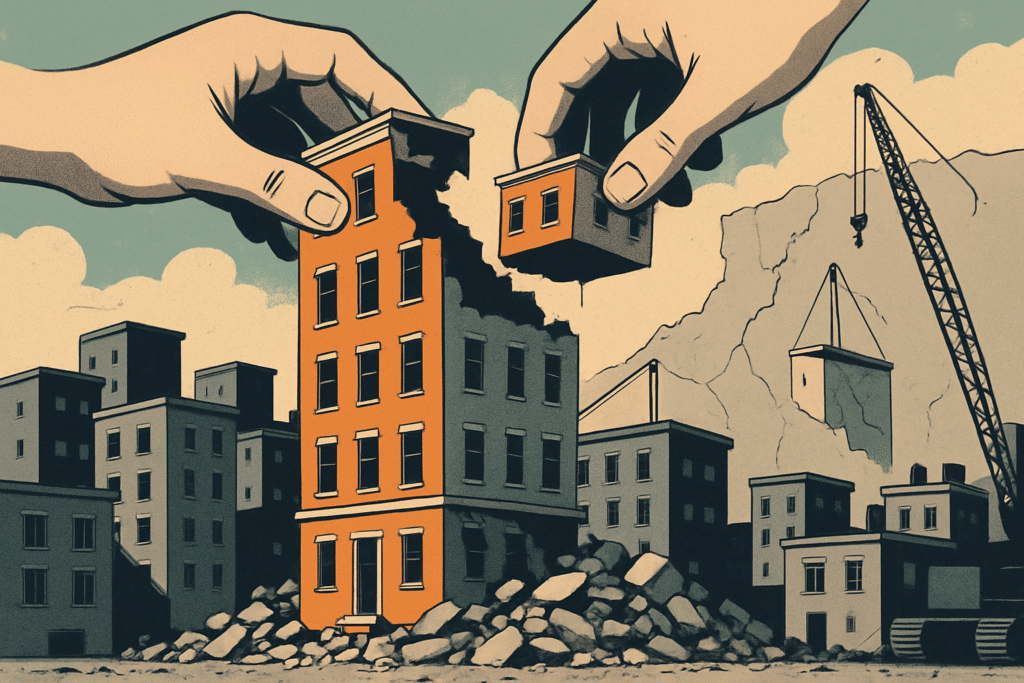

As Bauman emphasizes, ghettos are not merely geographical boundaries—they are social frontiers that maintain the distance between the privileged and the marginalized. Through this division, the image of the “Other” as a scapegoat is perpetuated, and genuine contact or understanding is systematically avoided. This separation is not only practical but also cognitive: it constructs walls between people—walls that hinder coexistence, empathy, and mutual respect.

The answer to such walls, as Bauman suggests, lies in shared experience. In physical and meaningful coexistence, in the creation of common spaces and experiences that gradually deconstruct prejudice. When the Other is no longer an abstract threat, but a neighbor, a classmate, a colleague, the fears born of ignorance begin to dissipate. Prejudice is born in the vacuum of ignorance and fades through interaction.

Hans-Georg Gadamer, in Truth and Method, offers a philosophical foundation for this process: to truly understand the world, we must recognize our prejudices, bring them to light, and reinterpret them. Prejudices are not inherently negative—they are structural elements of understanding—but they must be continuously re-examined. Authentic understanding arises from the fusion of horizons, the encounter of different cultural and historical perspectives. Only then can we acquire a fuller, more universal comprehension of reality.

Thus, the response to ghettoization is not isolation, but encounter. Not control, but dialogue. Not repression, but a conscious effort to understand and coexist. When we dismantle the walls that divide us—both tangible and symbolic—we pave the way for a society that is more just, cohesive, and humane.